Hooks, Forks and Tormentors: a brief illustrated guide

Geoffrey Smaldon & Jonathan Hill

Photography by Nick Goodwin Sports & Product Photography

Introduction: Little has been written on the subject of flesh hooks, flesh forks and toasting forks, more attention having been given to other domestic metalware such as cauldrons, skimmers etc. This purposely brief but well-illustrated account provides succinct information on mainly British hooks and forks from the 14th to the 20th centuries. Many examples are illustrated and references for further reading and research are provided.

A late 17th – early 18th century flesh fork. The function of the hole near the base is uncertain: one possibility is that the fork was intended to fit onto a stand of some kind.

Flesh hooks: Such hooks, which would have been used in medieval kitchens, were apparently introduced in the 13th century. They differ from later flesh forks in having two or three hooked iron arms projecting laterally at right-angles from a wooden or iron shaft. They were used for examining food items which were cooking in cauldrons over open fires.

Rarely encountered now, they can be seen in early illustrations such as the Luttrell Psalter (c.1340) and in a companion illustration to Chaucer’s ‘Canterbury Tales’ (1387 – 1400). Their relatively small size does suggest that other means of lifting large items into and out of cauldrons might have also involved sturdy flesh forks of a more conventional shape. Flesh hooks seem to have gone out of general use by the 16th century.

Rarely encountered now, they can be seen in early illustrations such as the Luttrell Psalter (c.1340) and in a companion illustration to Chaucer’s ‘Canterbury Tales’ (1387 – 1400). Their relatively small size does suggest that other means of lifting large items into and out of cauldrons might have also involved sturdy flesh forks of a more conventional shape. Flesh hooks seem to have gone out of general use by the 16th century.

Flesh forks and Toasting forks: Early references to flesh forks and toasting forks are scant in the literature but can be found, for example, in Shakespeare’s works (1564 – 1616) and in early accounts such as Randle Holme’s ‘Academy of Armory’ (1688) where illustrations 36 and 37 show ‘a forke or flesh forke’ and ‘two table forkes, or two toasting forkes’. An illustration from ‘The Cryes of the City of London’, first printed in 1687, shows a street vendor selling a flesh fork and fire shovel. Samuel Pepys (1633 – 1703) possessed a sixteenth century set of woodcuts of the ‘Cryes of London’ in which a vendor is selling somewhat stout two-pronged ‘toast’ng forks’. Later the engraver John Kay produced two illustrations of Lauchlan McBain, ‘vendor of fly jacks and toasting forks,’ in 1797 and again in 1815. He is shown carrying several long three-pronged forks in the earlier print and a single, more substantial, fork in the later illustration. Another etching of an unknown itinerant vendor dated 1815, by John Thomas Smith, shows him selling ‘ roasting jack, toasting forks, files or skewer’. He appears to be also carrying simple trivets and flat-iron stands.

It is probable that the evolution of the domestic hearth from down-hearth to bar-grate, hob grate and fire-basket in the 18th and 19th centuries led to accompanying changes in the design and use of flesh forks and toasting forks. Although it should be borne in mind that very few domestic implements had a single function, it is not difficult to see how robust iron flesh forks were more suitable for handling larger pieces of meat for transfer into or out of a cauldron, or roasting cuts of meat, birds or potatoes over the naked flames of a down-hearth. With the development of the bar-grate it was possible to toast and cook small pieces of food without being too close to the heat of a large open fire. Forks for this purpose thus tended to be lighter in structure and some later examples are designed to attach to the bars of the grate while in use.

Flesh forks are usually made from wrought iron or steel and have two, three or four tines, or prongs. Their length varies, most being between 50 cm and 75 cm and it is probable that even shorter utilitarian forks were also used to hold down cooked joints of meat ready for carving once they had reached the table. Variations in the shape of the shaft and handle of the fork can be found, with most shafts terminating in a flattened handle with a circular central hole for hanging. Forks with a flat terminal turned over onto the back of the shaft and into a hook are often continental or North American in origin. Determining the age of a fork from its shape is difficult as, if the fork was fit for its purpose, there was little incentive to make alterations to the design over time. Decoration was normally simple and achieved with a cold chisel, often when the metal was cold. In some cases, however, the detail and fineness of the decoration is an impressive example of the blacksmith’s skill.

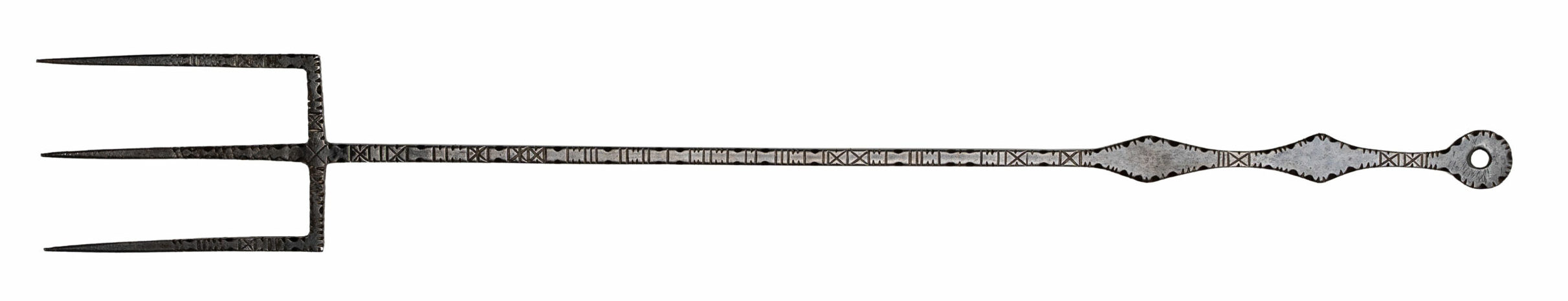

A finely-decorated 18th century fork of high quality.

Dated forks are rare but are useful in that they provide evidence of styles in certain periods. Early flesh forks made from brass or copper are seldom found; these softer metals would not withstand constant rough use and would also conduct heat to the hand more readily. Flesh forks with brass inlay and surface decoration are encountered occasionally, as are forks whose decoration suggests that they were love tokens or marriage gifts.

A copper fork showing a heart-shaped handle with initials.

Early accounts of flesh forks both in the UK and USA sometimes refer to them as ‘tormentors’, a term surprisingly still in use in a trade catalogue of 1902 and by Wallace Nutting (USA) in 1921. It is likely that this term was initially applied to flesh hooks, which bore a resemblance to the medieval torture hooks used to pull muscle from bone.

A sturdy flesh-fork bearing the date 1720: a rare feature.

The differences between flesh forks and toasting forks are not absolute and, as mentioned above, some interchange of use probably occurred and thus our current nomenclature for these forks is subjective. That said, it can be assumed that most toasting forks were lighter than flesh forks as the portions of bread, meat, and birds were small and did not require the strength of a flesh fork. Many toasting forks with three tines had the central tine raised above the lateral pair, this helping keep the item on the fork if it was of irregular shape. Forks with four tines arranged opposing each other are unusual and were thought to be used for roasting small birds.

A superbly-made flesh fork from the 18th century showing elegant form.

Many toasting forks have long wooden handles, the tines being an extension of an iron or steel collar which helped prevent the wood from the possibility of burning during the toasting process. Some fine 17th and 18th century toasting forks had silver collars mounted on long ebony handles; these were obviously not meant for rough everyday use in a kitchen. Copper toasting forks are known and are thought to perhaps have been made as gifts or tokens by workers in the copper smelting industry around Swansea in South Wales. Brass toasting forks of the late 19th – early 20th centuries were used both as functioning forks and decorative items, and were produced in their thousands by such companies as John Jewsbury and Pearson-Page in Birmingham: these are not included here. It is worth noting that Jewsbury also made convincing reproductions of a few early iron forks at this time, as did Wallace Nutting in the USA. Other ingenious devices are known for toasting or roasting small items on a bar grate in the late 18th and 19th centuries.

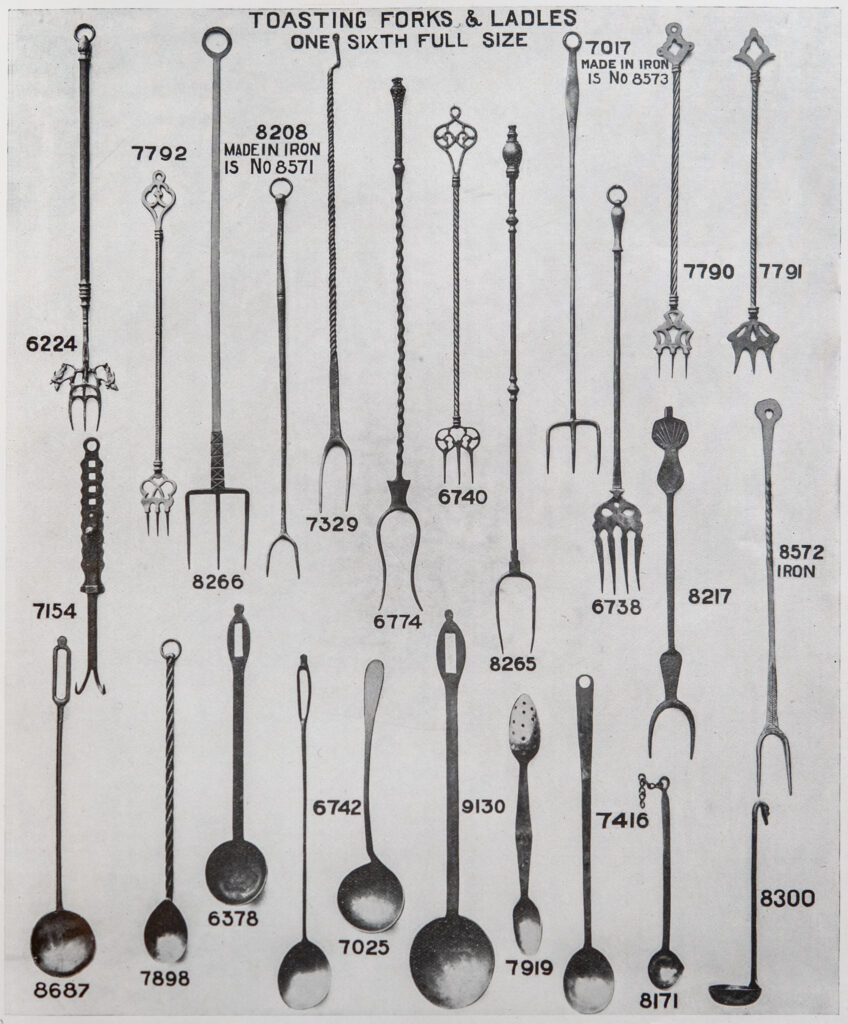

Page from the John Jewsbury catalogue of circa 1920 showing many reproductions of 18th and 19th century forks.

Examples of flesh forks and toasting forks: The sequence which follows is simple, and based on three sections:

- Flesh forks.

- Toasting forks.

- Unusual/specialised examples.

Flesh Forks

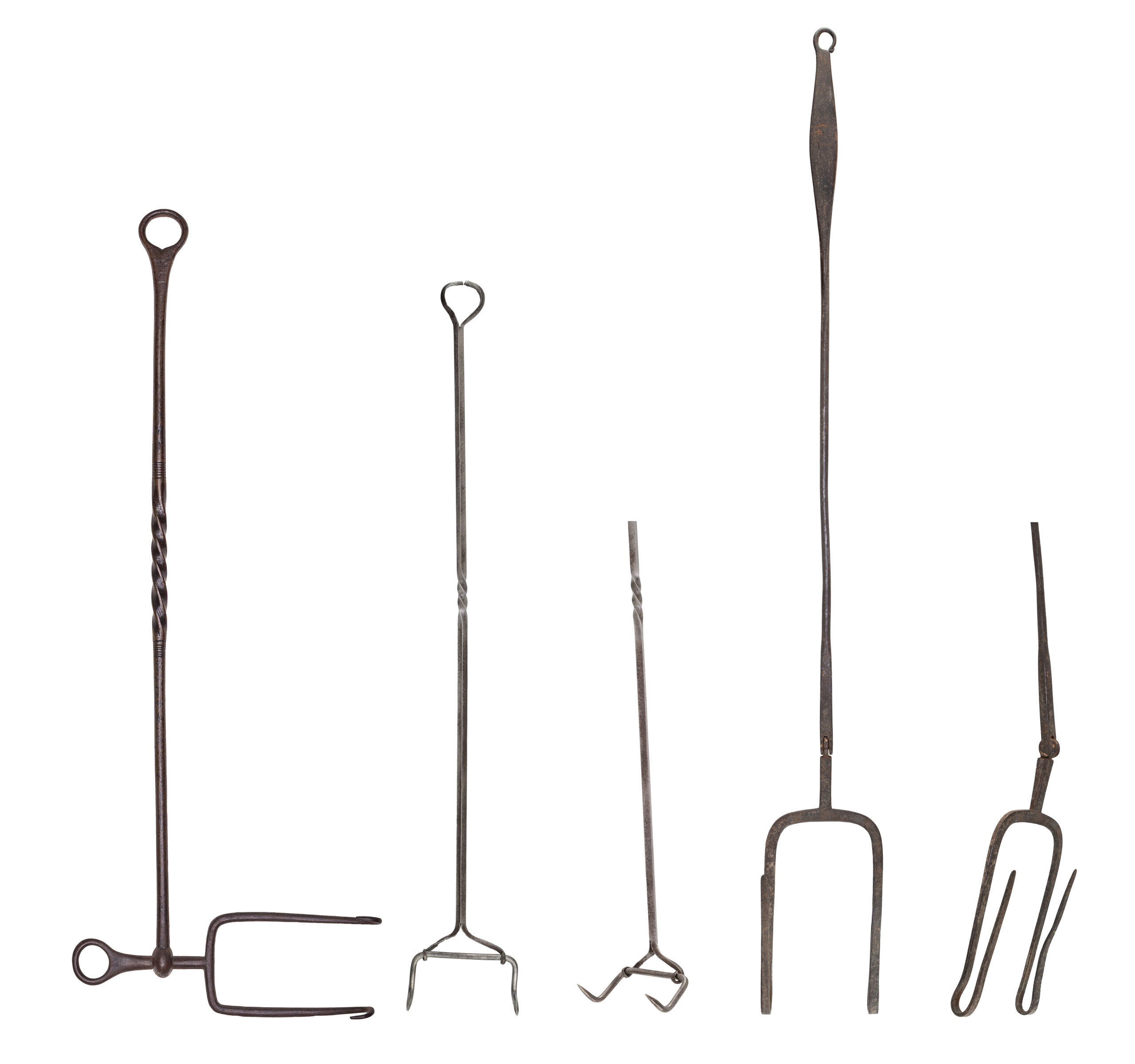

Four 17th-early 18th century flesh forks. The example with tines at 90 degrees to the shaft resembles an early “tormentor” fork in some respects.

Utilitarian wrought iron flesh forks from mid 18th – mid 19th centuries. Again, one resembles an early ‘tormentor’ fork and is difficult to date. The simple decoration on the shaft of one fork was easily made with a cold chisel but illustrates the desire to add individuality to the object.

Decorative 18th century wrought iron flesh forks, showing variations in shaft and handle design.

Wrought iron flesh forks, probably from the first half of the 18th century. Stout examples for heavy use, again showing variations in design.

Flesh forks with intricate scrolling. Such forks have been recorded from France and Scotland but other origins are possible. Dating from the 17th and 18th centuries, they represent the best of the blacksmiths’ art and craft.

Flesh forks and toasting forks from the 18th and 19th centuries. Raising the fork on two ‘legs’ allows the food to be cooked without the fork having to be constantly held. The rather elaborate shaft of one fork is unusual but suggests that it was not meant for heavy work.

Toasting Forks

Obviously lighter in construction than flesh forks, these toasting forks have long slender shafts and fairly delicate tines. Individual decoration can be seen, suggesting perhaps personal ownership and use.

Steel and wrought iron toasting forks from the first half of the 19th century. Again, lightness in the design of shafts and tines can be seen.

19th century long-handled steel toasting forks. Such long handles would allow the user to toast food without getting too close to the fire.

Toasting forks from the 18th century with inlay of copper or brass. Such inlays are rare and may carry the owner’s initials. The fork on extreme left may have had a dual purpose but is placed here to illustrate the brass inlay.

Miscellaneous toasting forks of mixed metals. Forks made of more than one metal are unusual: these examples show the use of iron, copper and brass.

These forks show the use of wood in the construction of shafts and handles. The long fork on the extreme left is unusual in bearing four tines and is thought to have been used for roasting small birds. The two forks on the right with turned wooden handles were made for the War Department in the First World War, despite their earlier appearance.

Further toasting forks using wood for handles or shafts. Probably late 19th – early 20th century.

Unusual Forks

Articulated toasting forks are usually 19th century in date, but an 18th century example is also shown here (right 2 photos). The articulation allowed bread to be toasted on each side by simply twisting the fork through 180 degrees.

The first of these brass forks appears to be meant for serious use and bears the name of the owner or maker. The others are rather fanciful, dating from the late 19th – early 20th century. Brass forks were rare before the late 19th century: after this time they were made in large numbers by companies such as John Jewsbury and Pearson-Page in Birmingham and became common household implements and decorative items.

Copper forks occur rarely but it is believed that many were by-products of the Welsh copper smelting industry which was centred in the Swansea Valley in the 18th– 20th centuries. The third fork from left bears an inscription ‘Miss Jane James’, suggesting a personal gift or similar. These forks are 19th and early 20th century in date.

More copper forks, including one made of intricately twisted copper wire. Such wire forks are difficult to date but are known to have been made well into the 20th century.

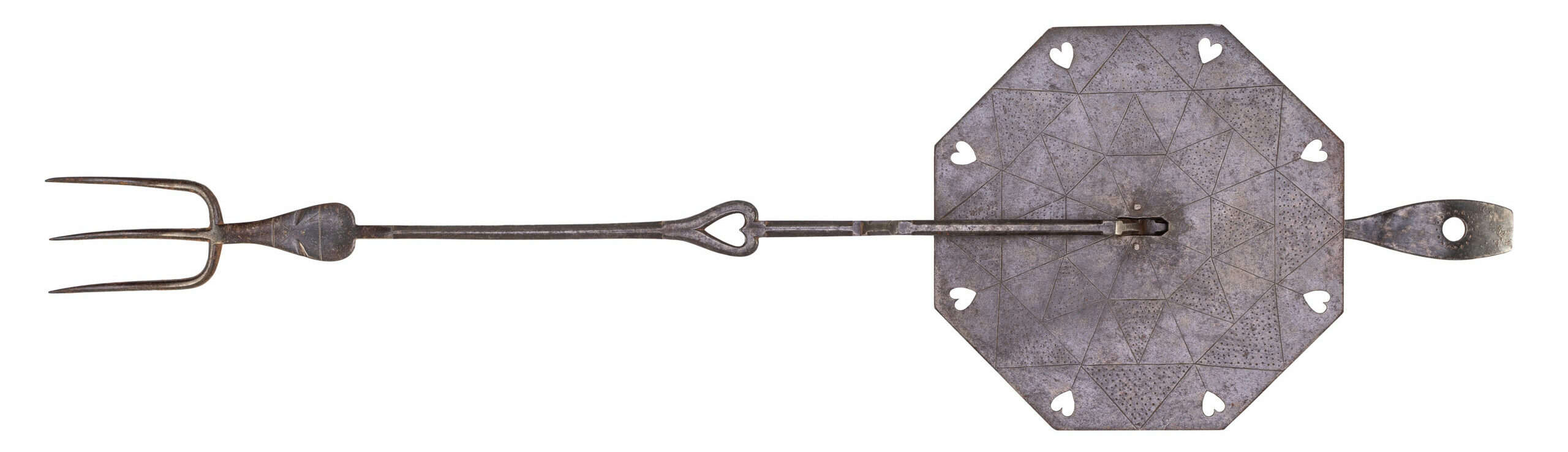

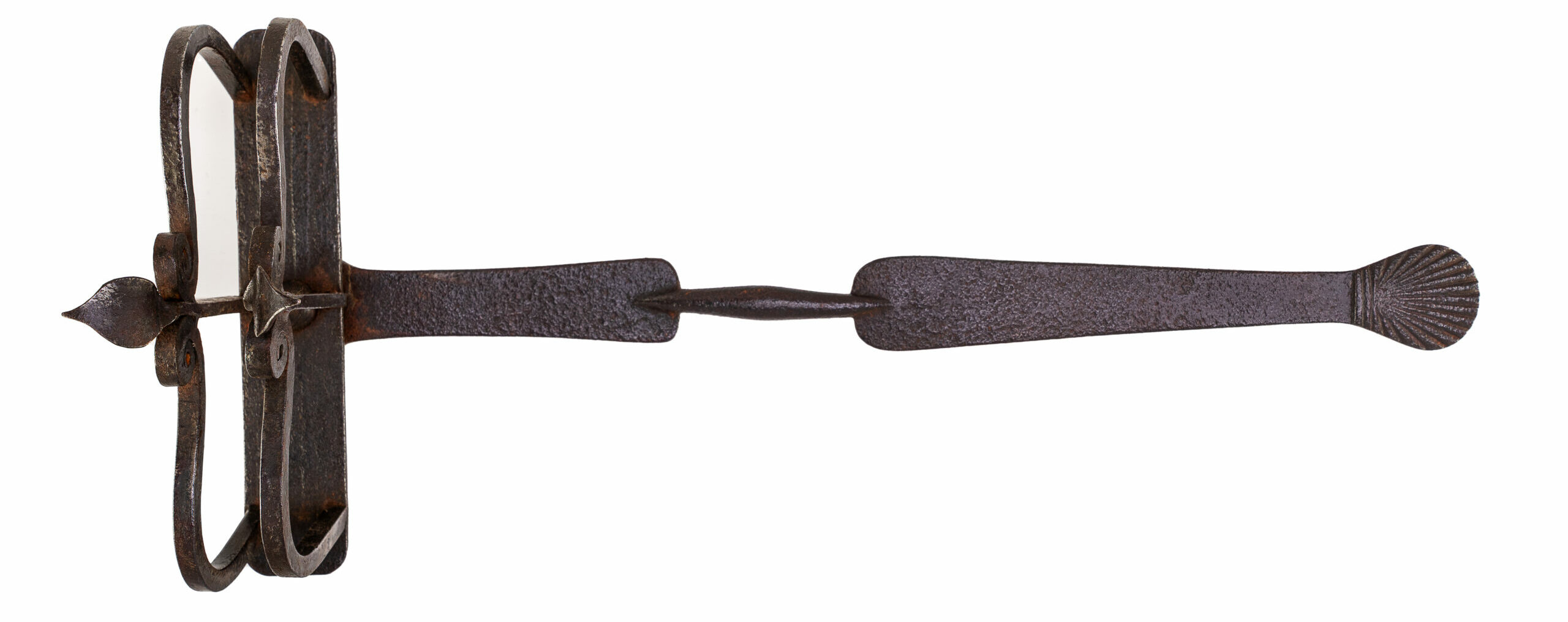

These unusual forks were designed to protect the user’s hand from the heat of the fire. Dating from the late 19th – early 20th century they show fine craftsmanship and are rarely found. The fork with an octagonal hand shield was designed by Ernest Gimson and is of superb quality.

Although not a fork, this elegant and well-made swivelling toaster is an example of another method of toasting bread close to a down-hearth fire. Probably 18th century.

A 19th century bar-grate fork which can be adjusted to vary the distance from the fire.

A complex 19th century mechanism for roasting or toasting.

A 19th century bar-grate toaster with sliding fork.

Further Reading

- Brears, Peter. 2008: Cooking and Dining in medieval England. Prospect Books. ISBN 1903018552

An extensive and scholarly account with comments on utensils interspersed with other text. Good account of flesh hooks and their use. - D’Allemagne, Henri Rene. 1924: Decorative Antique Ironwork. Dover Publications. ISBN 0486220826

A comprehensive illustrated catalogue of early ironwork in the Rouen Museum. See p. 389 for illustrations of 16th and 17th century forks. Minimal text - Deeley, Robert. 2011: The Cauldron, the Spit and the Fire. Gold Cockerel Books. ISBN 0947870733

Excellent photographic illustrations of several flesh – and toasting forks. Minimal text - Feild, Rachel. 1984: Irons in the Fire: A History of Cooking Equipment. Crowood Press. ISBN 0946284555

An excellent and comprehensive account. References to flesh forks occur in several sections - Fennimore, Donald. 2004: Iron at Winterthur. Winterthur. ISBN 0912724633

A well-illustrated account with considerable history on forks from the USA - Gentle, R. & Feild, R. 1994: Domestic Metalwork 1640 – 1820. ACC Art Books. ISBN 1851491872

Deals mainly with brass items and thus forks only feature once on p 227 - Haedeke, Hanns-Ulrich. 1970: Weidenfeld & Nicholson. ISBN 0297179101

Interesting account of ‘large forks’ being used when carving meat joints in 15th and 16th century Italy - Lindsay, Seymour. 1927 & 1970. Iron and Brass Implements of the English House. Alec Tiranti. ISBN 0854589996

Several illustrations and mentions of flesh forks and toasting forks from the 17th and 18th centuries. Illustrated with line drawings. - London Museum Catalogues. 1940: 7 Medieval Catalogue.

Good detail and illustrations of early flesh hooks - Luckett ,R. 1994. The Cryes of London: the collection in the Pepys Library at Magdalene College, Cambridge. Old Hall Press. ISBN 0-946534-31-4

- Nutting, Wallace. 1921. Furniture of the Pilgrim Century, including Colonial utensils and hardware.

Illustrations of two flesh forks described as ‘tormentors’ and stating that they were used to take meat out of the pot. Also illustrates three toasting forks. http://www.survivorlibrary.com/library/furniture_of_the_pilgrim_century_1921.pdf - Norwak, Mary. 1975: Kitchen Antiques. Ward Lock. ISBN 0706350146

Comment on flesh or meat forks and their uses - Plummer, Don. 1999: Colonial Wrought Iron: The Sorber Collection. Skipjack Press. ISBN 1879535165

An excellent and well-illustrated account of Colonial North American flesh forks, their making, decoration and geographical origins. - Roberts, Hugh D. 1981: Downhearth to Bar Grate. Wiltshire Folk Life Society. ISBN 090775600X

Well-illustrated account covering hearth utensils but scant mention of flesh forks and toasting forks. - Schiffer, H., P. & N. 1979: Antique Iron: A survey of American and English forms, fifteenth through nineteenth centuries. Schiffer Publishing. ISBN 0916838269

Several examples of flesh and toasting forks illustrated on pp. 242 & 243. Text minimal - Weinstein, Rosemary. 1988: Kitchen Chattels: the evolution of familiar objects 1200 – 1700. Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 1988. Prospect Books. ISBN 0907325394

A good account of early flesh hooks and their variations

Useful Websites

- V&A Museum, London. A 17th century Italian toasting fork. Silver mounted ebony 18th century toasting fork plus illustrations of other silver-mounted forks.

- British Museum, London. Illustration of early Romano-British flesh hook.

- Museum of the Home, London. Illustrations of seven forks of varying age and pattern.

- National Museum of Ireland, Dublin. Note on the use of toasting forks.

- Randle Holme’s ‘Academy of Armory‘. Holme describes a ‘fire fork’ and a ‘flesh fork’.

- Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, USA. Excellent photographs of nineteen forks identified as European, Spanish, French and American. Minimal text accompanies each.

- Powerhouse Collection, Australia. Photograph of cooking fork ‘tormentor’ with one prong turned back 180 degrees. Date given as 1890 – 1920.

- Medieval and Renaissance Material Culture. Extensive information on flesh hooks with further references.

- Swarthmore College: ‘How the fork got its tines’. Deals mainly with table forks but some observations on flesh forks.

- Manuscript Cookbooks Survey. Illustrations and brief details of mainly US flesh forks and cooking forks. Collated from books ‘begun by the year 1865, the effective end point of the long transition from hearth cooking to stove cooking’. (Items 583, 1140, 1141, 1142, 1155, 1339, 1347)

- Bonhams: The Oak Interior, including the E. Hopwell collection. April 24th and 25th, 2013. Pages 74 – 77 illustrate and describe several unusual flesh- and toasting forks. (Lots 305, 306, 310, 312, 314, 317, 319, 322)

- Spitalfields Life. The Pepys collection of ‘Cries of London’.